COVID: A catalyst in HEI leadership?

This thought piece aims to share reflections following one of the most transformational periods in our sector’s long history, and to explore how the pandemic may shape its future.

As with almost every industry across the globe, Higher Education in the UK has been significantly altered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The way in which staff and students live and work has fundamentally changed, and we are unlikely to return fully to previous ways of working. In 2020 universities demonstrated great resilience and dynamism by rapidly addressing the challenges associated with the pandemic. This necessitated enormous commitment from senior leaders on both sides of the board table.

The almost overnight adoption of technology enabled transformation to happen apace, with innovation in the delivery of education near the top of the agenda for most institutions. As universities move from the reaction and resilience phase to the recovery phase of the pandemic, sector leaders have started to focus on the medium term, reassessing strategic priorities and working to address the imbalances caused by the pandemic.

In many ways the pandemic accelerated existing sector trends. Challenges facing the sector were amplified as universities were forced to adapt to operating within the context of a global health crisis. Many across the sector felt and still feel that the pandemic has enabled institutions to deliver positive change at a greater pace.

For this piece, we explore the extent to which COVID-19 has driven and accelerated change within the sector. We also investigate the implications for HEI leadership from several angles including governance, strategy, personal qualities and organisational structure. In Spring 2021, we consulted with both vice-chancellors and chairs from a range of Higher Education institutions across the UK. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to those who have graciously given up their time to share their thoughts and experiences with us.

Chapter 1

Reconstituting HE institutions

Home is where the office is

The initial tsunami of COVID-19 left many reeling, and universities – communities founded on human interaction and engagement – facing the challenge of continuing to function against a backdrop of local lockdowns and global paralysis. The safety and wellbeing of staff and students were priorities that demanded swift and largely unprecedented changes – especially a shift to online learning for students and working from home for staff.

We moved overnight from a solid, to a liquid, to a gas with particles all over the place: we need to reconstitute as an institution.

Forced to adapt in order to survive, universities found themselves able to put in place measures that for many had been under discussion for years, giving staff and students access to the technology that would enable flexible working arrangements, remote meetings and off-site learning and teaching. The changes were wide-reaching and have already taken root.

For many universities, this has represented fundamental change in the functioning of an academic community. For the world at large, however, the shift towards digital integration and agile working has been a reality for some years. Has COVID-19 been the catalyst that has brought higher education into line with the world it serves?

More speed, less haste

The change agenda has been accelerated to warp speed.

Perhaps the most striking legacy of COVID has been a mandate to think and react quickly: ‘with the arrival of COVID, the executive suddenly had to take decisions very rapidly with imperfect information’, and in ‘days rather than months’, often changing from one day to the next in line with shifting government legislation and regional advice.

In a world where decision-making is traditionally a measured, consultative and consensual process, the need to react to the rapid pace of life in the pandemic has resulted in approaches that have ‘had to be much more autocratic’. These approaches feel much more akin to the corporate world, typically more ‘fleet of foot’, than academia – and senior team members with no experience beyond the sector have had to adapt to profoundly different ways of working.

COVID has shone a light on the cracks in many organisations. It was clear to many early on, that the role of the board was one that must be agreed upon and stuck to right from the outset. For most, it was self-evident that the board should not be running the organisation: that is the job and function of the executive. However, it was acknowledged that this has not been easy learning for some non-executives, especially in a time of such crisis. Yet, this attitude had to be overcome as quickly as possible, and the boards that considered their response to have been most effective were those that put fluidity and support of the executive as the absolute priority.

Whether it is innovation, acceleration of the inevitable, or just clarification of what really is important, there was an overwhelming consensus amongst interviewees that COVID has brought emphasis to the fundamental priorities in the boardroom. We shall explore these priorities further in later chapters.

Qualitatively, it has been very demanding on the executive. They have had to make a lot of decisions very much faster than they have been used to.

While the pace of decision-making has proved challenging for some, others reported that their team has found the speed and agility empowering: ‘there’s a real adrenalin rush from the power of that decision-making’. It has granted senior leaders freedom – albeit perhaps temporarily – to lead more decisively and make the decisions they feel are right for their institution. Our interviewees highlighted however, that these decisions must never be made lightly; there must always be a sense of ‘matching empowerment with accountability’.

The challenge of maintaining morale

Perhaps surprisingly, many have found that the experience has brought the executive closer together: the need to respond rapidly to immediate challenges with conviction has for them created a real sense of camaraderie.

There have been serious silver linings in the clouds that we have experienced.

Everybody reported significantly increased interaction, with daily meetings of the senior team commonplace during the early days. Communication was seen by all as vital at every level, especially when decisions were being taken swiftly and with less consultation than most were used to.

The likes of Zoom, Teams and Slack were referenced as key to agile working, staying connected and regular communication. Instant messaging and video calls meant that the right people could be consulted on relevant matters without waiting for scheduled meetings.

Many however highlighted the other side of the coin. The lack of physical interaction meant that nuances were missed – ‘I’m realising how many conversations happen over coffee’. Although technology allows organisations to function without undue risk to team members, it also makes it much harder to read body language or to know when somebody is uncomfortable with a suggestion but cannot find space to speak up: ‘working on Zoom or Teams is no substitute for sitting in the same room as someone and chatting away’.

More generally, university leaders recognise the acknowledged fact that spending hours at a time on video calls and in digital meetings is very draining, and many suggested that the innate flexibility and natural ebb and flow of working life had been pushed to the limit. For some, the stress of adapting to new ways of working combined with pressures outside working life had been an unimaginable stretch: ‘there’s a deep sense of exhaustion – people are feeling disempowered by the virus’. As a result, a greater focus has emerged on wellbeing across both staff and student populations – a theme to which we will return later.

Bringing new members into a team has been particularly testing. Challenging at the best of times, joining a complex and multi-faceted organisation such as a university has been made more daunting by remote working, and it will be important for leaders – some of whom have themselves been appointed during lockdown through entirely online processes – to create the mechanisms that will ease the path to integration.

Championing change

The old normal is never going to happen – we can’t go backwards.

As the slow transition to a post-pandemic recovery phase begins, university leaders, both executive and non-executive, must more than ever give visible support and leadership in the disruption that will inevitably persist for some time to come.

Key to this will be ensuring that open lines of communication with staff and students remain in place. All our interviewees emphasised that this was a vital consideration when managing any change activity: ‘the advice is always to communicate a lot’. Indeed, one interviewee highlighted that in their experience ‘in retrospect, when reflecting on what you could have done better, it’s always to communicate more’.

It is important to present change in a positive light. All the leaders to whom we spoke agreed that successful change relies upon having people engaged with and bought into the programme. In many ways disruptive, challenging and daunting, the pandemic has also presented an opportunity to refresh established ways of working – a chance to ‘rip up the old rule book’ and take a fresh look at everything from detailed processes to overarching institutional structures.

The pandemic has shown us that different practices, including remote and flexible formats, can work successfully at scale. The workforce model of the future must be flexible, adaptable to changes in demand and able to accommodate the evolving needs of staff and students.

This responsiveness is especially important for the long-term wellbeing of staff. The effects of the pandemic stretch far beyond the workplace, particularly for those juggling work with home schooling, caring for relatives, health concerns and other worries. Traditional support mechanisms have come under severe strain from social distancing, travel bans and a requirement to work from home.

The leaders who will see the greatest successes as we begin to emerge from the pandemic will be those who acknowledge the cumulative impact of working under these stresses and create an environment where wellbeing – of students and staff alike – is a real priority.

Chapter 1: Brief notes from the search perspective

Many institutions paused senior hires into the executive at the beginning of the pandemic, largely to refocus time and energy on immediate concerns. As the sector has moved from crisis-response mode through to recovery, and now towards a medium to long-term strategic planning phase, universities have reflected on the impact of the pandemic on their senior structures and governance. This has affected the profiles and portfolios of those roles – more on that later – but also the softer skills being sought by selection panels and nominations committees, particularly at vice-chancellor level.

Whilst they have always been important aspects of leadership at the helm of a university, attributes such as the ability to lead through a collaborative and engaging leadership style, capacity to build partnerships closely allied to institutional strategy, and perhaps the need for a high level of resilience alongside a calm and robust character have come to the fore. We had seen a general shift in this direction for vice-chancellor appointments in recent years, from a more directive ‘lead from the front’ to a more ‘primus inter pares’ style of leadership. This is just one example of COVID catalysing a trend in higher education leadership.

Chapter 2

Strategy-setting for the future

Back to the drawing board for strategy?

The job of the executive team is always to adapt our priorities – the pandemic has just concertinaed this.

Perhaps the most vital role of any organisation’s leadership team is setting the overarching strategic direction. This is no less true of a university than of any other business, and many higher education leaders are now being forced to re-examine strategies established prior to the pandemic to ensure they are still relevant for the changed world in which they are now operating.

Dealing with the day-to-day challenges of COVID, particularly in an environment of ever-changing governmental advice and legislation, has been an overwhelming task over the last year. As a result, there has been clear delineation between what is mission critical and what can be moved further down the agenda. There must be a clear line between the immediate, medium and long-term priorities.

We asked our interviewees whether these priorities looked different now from early 2020. While some leaders acknowledged that there has been a temporary pause in actively driving strategy throughout the pandemic, the consensus was that overarching strategic direction remains, in the most part, unchanged. As one interviewee stated, ‘an external event – even one as vast as a global pandemic – shouldn’t alter your values’. Rather, most agreed that they now face ‘more a programme of reprioritisation than a strategic rewrite’.

Student numbers holding steady against the storm

We considered everything from bad to god-awful to cataclysmic.

Once the initial challenges of the pandemic had been met, the pressing issue for many institutions was admissions for the autumn of 2020. Initially, many said that planning was focused on a worst-case scenario, in which numbers for both home and international students suffered significant losses, thereby significantly impacting finances.

Caution was urged by some leaders, who had witnessed universities lowering entrance standards in order to maintain numbers. They argued that since this had already been accommodated by government adjustments, universities were not necessarily trying to level the playing field for students whose grades suffered as a result of COVID, rather they were aiming to shore up enrolments to fill the gap left by EU students as a result of Brexit. In effect, they argued, universities were aiming to backfill with home students.

This, our leaders warned, could potentially have a knock-on impact on the lower-ranked universities as the larger and more prestigious universities fight to take on a greater market share to compensate for the loss of EU or international students.

Despite the dual perils of Brexit and COVID-19, however, neither international nor home student numbers seem to have been as heavily impacted as models were predicting. Indeed, many universities even fell victim to oversubscription following the A-level regrading in England: ‘we ended up with more students than we could accommodate – people had two goes at getting it right’.

Many had predicted international student numbers falling by as much as two thirds, and have therefore found themselves in a relatively strong financial position thanks to intakes remaining comparatively strong: ‘we did much better here than when we planned our budget and currently are actually on track to have a surplus relative to the budget we formulated based on the revenue position’.

Despite this optimistic vantage point, there was broad acknowledgement from leaders that the future remains, in some ways at least, uncertain for the sector therefore risk analysis should continue to be robust and comprehensive.

A mission critical digital evolution

In 2020, universities were forced to move swiftly to accommodate a mode of pedagogy that was not until that point universally embraced or understood. Online learning formats were adopted almost overnight by institutions the length and breadth of the country with a dexterity that surprised even our interviewees: ‘before this, I would have been pessimistic about the ability of any university in the UK to make a move quickly, but everyone has impressed themselves and everyone else in terms of their agility’.

It’s one thing to shove all your course content online – doing it by design is something rather different.

However, given online and blended learning is set to stay, all agreed that more support must be given to those delivering it. One of our interviewees argued that ‘many think teaching online is easy – it really isn’t’: academics must be supported not just in terms of the technology but also in how to develop modules and create content specifically designed to be taught online. It is abundantly clear that universities cannot just present a digital version of what would be provided in an in-person lecture – ‘if we curate it and build it for online, rather than just providing online that which would have previously been provided in a lecture theatre, that is a much better opportunity’.

There will, of course, always be a demand for in-person learning, however the success of the new approaches brought about in reaction to the restrictions of the pandemic has opened up the UK’s higher education sector in ways that might have seemed impossible pre-COVID: ‘our eyes have been opened as to the scope for distance learning, even for courses where you would never have thought it possible’.

There are many things that we’ve done that we had already seen as being the future, the future has just come a lot quicker than we’d anticipated.

Online learning presents huge opportunities for universities to move away from the traditional ‘ages and stages’ structure that assumes a person goes to university straight from school and graduates before entering the world of work. Rather, flexible and distance learning options give universities the chance to become more porous and encourage life-long learning (which of course many do). This introduces new potential ‘customer’ bases for universities, broadening their appeal to other markets.

For those institutions with a particular disciplinary emphasis, the move to digitally-focused learning has presented a other challenges given the importance of lab-based work. This challenge has, however, been met with innovation, for example virtual field trips delivered to geology students or engineering ‘lab in a box’ concept projects, designed to be packed up and delivered to each student at home.

Another benefit of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the enormous opportunities that have opened up around research. Throughout the last year, people have been thinking, working and acting in much more collaborative ways. For example, virtual conferences have replaced in-person events, lowering the sector’s carbon footprint and making collaboration smoother, lower-cost and fundamentally easier to do. Indeed, our interviewees reported a real sense of individuals wanting to step up and make a difference through their research. The key as we move forward will be finding a way to capture this attitude and outlook, and maintain the momentum. The need for the translation of research into real-world impact has never been greater. The speed at which this can be achieved has also been catalysed by COVID. The speed of the journey through the development and delivery of the vaccine is an example of this witnessed by the world.

Trading bricks and mortar for the digital world?

The idea that we’ll be concerned about academics being on campus five days a week, week in, week out is laughable now.

Traditionally, a significant proportion of a university’s capital is spent on bricks and mortar. For most institutions, that encompasses a mix of student accommodation, teaching and learning facilities, staff offices and student facilities. In fact, before the pandemic, the UK’s universities spent more than £3.5bn a year on capital developments, according to data from the Association of University Directors of Estates (AUDE).

One interviewee stated that when they first stepped into their role with their university, almost all the capital was allocated to bricks and mortar. Moving forward, they imagined that capital should be more evenly divided between technology and physical infrastructure, and they acknowledged that there has been an acceleration in this shift as a result of COVID.

As a result of the success of both flexible working and blended forms of learning, it seems likely that the way in which campuses are used is set to change forever. Indeed, many of our interviewees reported that major projects had been paused, postponed or cancelled as a result of COVID-19 and the shift in priorities this has triggered.

There’s no turning back the clock on the shift to digitally accessible content – students vote with their feet in terms of how they want to participate.

While universities have clearly demonstrated their ability to adapt in times of need, they must now establish a blended approach able to deliver the best of both an on-campus experience and a digital learning environment. Our interviewees were generally of the opinion that universities would no longer need such large physical estates as previously: ‘not because we expect to have fewer staff and students, but we expect that for both there will be more flexible modes of attendance’.

As we look to the university campuses of the future, the ability to deliver online teaching effectively will be towards the top of the list of priorities. Many of our interviewees reported that online lectures have seen significantly better attendance rates than in-person lectures. Students, on the whole, will however, still take huge value from the spatial and interactive elements of being on a campus.

For most students, the university experience is not wholly focused on the academic (as Bill Bryson famously said during a graduation ceremony as Chancellor at Durham University: ‘don’t let your degree get in the way of your education’) and there was a general recognition that ‘this is not the university experience students expected: they’re getting restless’. Lack of clarity over government advice, changing mandates and forced last-minute decision-making have all fed into this sense of dissatisfaction, and it will be vital that the student voice is both heard and appreciated as leaders shape their plans for the future. Our leaders were very clear that students must be at the heart of the decision-making, stating ‘we can’t go back to the way things were, but we desperately want the students back’.

Of course, student-facing spaces are just one side of a university’s estate: the other key consideration will be space for staff and academics. While the increased flexibility of working from home has been embraced by many, there are also many roles that will continue to require a physical presence on campus, whether full-time or on a more flexible basis. In a sector with such heritage, there will still be some resistance to change according to many of our interviewees. Indeed, one chair summarised a point that was raised by many, stating: ‘the challenge will be weaning academics away from private offices’.

As university leaders look to redress and reprioritise strategies to ensure they are fit for the future, the role of property and estates management will no doubt be a significant consideration. Having the right experience at a senior level will be essential to manage this change and ensure that higher education institutions invest correctly to guarantee success for the future.

Chapter 2: Brief notes from the search perspective

Building consensus around new or developing strategies through consultation with staff and students – including at an institutional level – is becoming the norm. This is arguably another trend catalysed by COVID. Strategic priorities such as sustainability, diversity and inclusion, and staff and student wellbeing were building momentum ahead of 2020, though the pandemic has arguably thrown these priorities into sharp relief, with universities now being exceptionally clear about how they are developing and delivering strategies to meet these challenges.

Another strategic priority that came through our consultation very strongly was how institutions leverage their estate. Over the last 3 to 5 years, we have observed an empowering of the IT function that has shifted its responsibilities from being purely a back office ‘reactive’ function, towards a strategic enabler, critical to delivering a university’s strategy. COVID has catalysed this trend. A clear example of this is the shift from the role of a ‘director of IT’, usually reporting into a COO or equivalent and not on the executive team, to a ‘chief digital officer’, ‘chief information officer’, or ‘executive director of infrastructure’. An increasing number of universities have promoted already or are looking to promote this position to the executive, and to source talent from more technologically advanced and capital-rich industries.

Chapter 3

Guidance for governance

A line in the sand: governance and the executive

Like all those involved in the upper echelons of university leadership, chairs and members of governing bodies contributed a significantly increased amount of time throughout the pandemic. Despite a much greater number of board and committee meetings, it was reported that typically meetings were much shorter and ‘much more operational in nature than we would usually involve the governing body in, just to keep them confident and satisfied that we had all these matters in hand’.

We’re trying to tread a middle ground between an utterly exhausted executive team and a hawk-eyed board.

As the ultimate guardians of an institution’s reputation and strategic direction, it was perhaps predictable that university councils and governing bodies felt a greater sense of responsibility throughout the pandemic. Some senior leaders on the other side of the board table felt this keenly, with one vice-chancellor advising boards to ‘tread a bit carefully to make sure senior management do not spend so much time explaining to council what’s going on that they don’t have time to do their job!’.

The most important person at the university is the vice-chancellor, but I’ve heard stories that have made me think some chairs think that they’re the most important person at the institution.

Regulation: a help or a hindrance for governance?

Good governance must continue to be at the heart of the UK’s higher education sector as we look at how the sector should function to make it fit for the future.

For many, operating within the parameters of the CUC’s codes was deemed ‘a bit clunky but not overly burdensome’. However, others suggested that the code is no longer fit for purpose: they argued that the landscape has changed to such an extent that a code that has been adapted and amended over years is no longer able to do the job required of it. Rather, there was a call for the current regulatory framework to be replaced with guidance built for the new world in which universities now find themselves operating. This code would acknowledge the growth in responsibilities placed on the council and clearly delineate where management ends, and the non-executive begins.

There’s a blurring of the lines between management and governance as the requirements of governance continue to increase.

The future face of HE governance

Our interviewees generally agreed that university governance structures need an overhaul beyond the cyclical governance reviews that institutions currently undertake every few years, but that there is perhaps too much going on for this to be a priority at present. Many suggested that university governing bodies have grown too large and that they have too few lay members to give a balanced perspective. Some interviewees went as far as to suggest that overly academic-focused boards can be narrow in their thinking and prone to adopting a path of least resistance: ‘how it has always been done’.

Generalists are coming to the fore at board level – we want people with broad perspectives.

Something all interviewees agreed on whole-heartedly was the importance of introducing diversity at board level. Bringing in a diversity of background and experience was thought to be vital to ensuring good governance in the future. Clearly any board needs to ensure that there is a representative skillset, capable of providing balanced and well-reasoned insight into the strategic challenges the institution faces.

Some of our interviewees argued that the model of unpaid lay membership is not sustainable when ‘universities are realistically quite big and professional businesses’. This suggestion did, however, come with a word of caution: ‘if you start paying there is a risk you’ll get different people coming in and changing the dynamic between the board and the vice-chancellor’.

Over the last year, there has clearly been a transformation in the way in which university governing bodies function. Whether this is a direct result of COVID-19 or whether the implications of the pandemic have acted more as a catalyst, accelerating change that was already well under way, remains a point of great debate. There can be no doubt, however, that many of the ways of working made commonplace by the pandemic are here to stay, whether that be for executive members of staff or governing bodies.

Chapter 3: Brief notes from the search perspective

2021 has witnessed a sharp rise in the number of UK HEIs looking to refresh and add skills to their boards. The reasoning is twofold: firstly, many members of councils and courts whose terms technically finished in 2020 were asked to extend to provide stability through the pandemic; secondly, chairs are looking to bring in or reinforce particular skillsets around the board table.

There are several trends in respect to this second reason. Universities had been looking to add digital transformation capability to their boards for a number of years prior to the pandemic as they looked to capitalise on blended and distance learning opportunities and to enable a modern digital infrastructure to support strategies in teaching and learning, and the student experience. COVID has made bringing this capability to the board essential, rather than simply advantageous, given new delivery models in teaching and the transition in how staff and students engage with a campus.

Those from large technology businesses and consulting firms with expertise in smart cities and technology’s role in the place agenda are highly sought after. There are comparable trends in respect to digital marketing, major programmes, and ‘regulation’ experience that are also increasingly sought after.

Many institutions have made a clear commitment to increasing the ethnic diversity of their governing bodies. Whereas previously, selection panels and councils felt broadly comfortable when they had an ethnically diverse list from which to choose at an early stage in a search (feeling, if you like, that that ‘box had been ticked’), now there is a demonstrable commitment to selecting these diverse candidates to join university boards, which from our perspective is a very positive trend. The question does, of course, reach beyond the board, and a university needs to be very clear on its institutional narrative and strategies around diversity – including academic promotion and attracting a diverse staff and student community. The pandemic has, arguably, thrown this into sharp relief, with many universities now communicating exceptionally clearly about how they are addressing the issues and championing diversity.

Chapter 4

The changing face of executive leadership

It gets lonely at the top

Be it vice-chancellor, president, principal or chief executive, the most senior leaders of universities have found themselves in an unenviable position over the last year. They have been pushed to the limit, keeping their institution functioning against all odds and against a backdrop of increased scrutiny, financial pressures and a vastly increased workload, not to mention the personal challenges posed by life in a global pandemic.

In addition, the scope of the role and the responsibilities that go with it are continuing to grow. Our interviewees suggested that as we move forward, there may be argument for spreading some of this load across a small team of talented senior leaders. This would allow the vice-chancellor to be more focused on the overall strategy for the university, looking beyond the day-to-day operations, as is already the case in some institutions.

There is also a real need for institutions to give careful consideration to succession planning and investment in skills and professional development further down the organisation. It was broadly acknowledged that due to the speed of decision-making and the importance of reacting quickly throughout the pandemic, ‘COVID has been very management heavy – we need to start making investments further down’. While senior leaders have shouldered the brunt of the decision-making strain throughout this period, it is vital that organisations recognise the extent of the strain, both personal and professional, and ensure that adequate investment in support is made. The ‘staff experience’ has already become part of an executive leadership role title at one institution, alongside the traditional PVC for ‘student experience’.

Faces for the future

As we have explored throughout this piece, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented challenges for senior leadership in the higher education sector the likes of which have never been seen before.

We’ll need to enrich the aggregate skills mix and our ability to work cohesively as a team.

Our interviewees were asked whether they thought there would be changes to their leadership teams directly because of COVID. They were asked to consider both the skills mix and any specific new roles that might be arising as a result of the challenges presented by the pandemic.

We’re planning a brainstorming session with disruptors from the digital and business worlds: we know we need to reinforce our skillset here.

Significantly, many of the respondents highlighted that prior to the pandemic they had already begun to review and assess the roles and responsibilities both at a senior leadership level and across their institution. Interviewees argued that any well-managed institution should have this on their agenda on an ongoing basis, not only in response to exceptional circumstances. For almost all, this included a heightened focus on digital expertise as a response to the modern world, not just as a reaction to the pandemic.

Logically, structure should follow strategy.

Many also suggested that they were looking at a more professionalised academic structure, including consolidation of administrative functions. There was a suggestion that this is particularly challenging for the more established institutions which can lack the flexibility of a modern university. Recently established institutions are, by nature, more ‘business-like’ and do not have the same cumbersome structures. It was felt that many older universities had grown almost unchecked and had therefore developed exceptionally complex, multi-layered structures that are difficult to unpick and reinvent.

For many, however, the challenges faced throughout the pandemic have presented an unexpected opportunity, highlighting existing fault lines or skills gaps within leadership teams. This has allowed for teams to be developed either through recruitment shaped around specific skillsets or through tailored professional development and skills-based training.

For both the executive team and council members, an awareness of the evolving digital landscape – which many interviewees suggested was not as strong as it should be – will be vitally important. Function expertise, however, is typically considered less important than a broader understanding of how things are inter-related and influence one another: universities are not necessarily looking for ‘digital tzars’ to join their team, but rather to ensure that there is a broad awareness of how digital technology can be integrated into the day-to-day workings of the institution.

It’s what’s underneath that counts

The technical skills are learnable, what’s needed are skills you can’t learn.

While professional skills and experience in fields such as digital provision, IT and estates management were highlighted as being important factors for senior leaders to be able to bring into their teams, many highlighted that the pandemic has reinforced the importance of ‘softer’ skills in leaders, as we allude to earlier in this piece.

Personal and interpersonal skills such as resilience of character, understanding, empathy and sympathy were all repeatedly referred to as our interviewees discussed how their teams had coped throughout the pandemic. In times of hardship, these were the skills that kept the team functioning well together and able to work in a way that was efficient, resilient, and proactive.

It was highlighted repeatedly that while across the UK, senior university leadership teams have, thus far, managed to function and support their institutions through the immediate challenges, there may well be additional changes required as we enter the post-pandemic recovery phase.

For now, it is just too soon to know and the path ahead remains something of a mystery. For senior leaders, ensuring that the university’s strategic direction is well established and tailored to supporting the success of the institution is the first step. As one interviewee put it, ‘we’ll get to that when we work out what it is we’re trying to deliver!’

Chapter 4: Brief notes from the search perspective

Higher education has witnessed some sector-wide trends in the evolution of leadership structures. For example, prior to the pandemic an increasing number of universities added a provost or sole deputy vice-chancellor to their top teams in recognition of the fact that the vice-chancellor’s responsibilities were ever more external in nature. This was heavily tested in 2020, in some cases emphasising this distinction, and in others, bringing the roles closer together. Another trend, perhaps on a more gradual timeline, has been the emergence of a ‘super COO’, to whom all professional services units ultimately report.

More interesting, however, is the steady departure from the idea of a ‘standard issue’ executive structure. This is set to continue with more institutions creating roles that are unique in the sector with a brief that is specific to needs, geography, culture, or profile of that particular university. We have also observed some more tangible and current trends that have been catalysed by COVID, such as the need for PVC/VP Education appointees to bring some level of digital competency, or the rationalising of the PVC/VP International role in light of a university’s global priorities following the pandemic (and, arguably, Brexit). On another note, whilst there has been less enthusiasm to explore left of field, non-academic candidates for vice-chancellor appointments than was the case pre-2020, there has been a marked increase in the appetite to bring in talent from other sectors for professional services leadership roles.

It will be increasingly important to articulate exactly what the university expects of a role holder when appointing new talent into a top team whether from the sector or not – simply reading the job title as a basis for understanding the particularities of a specific role in a specific university will fall well short in a post-pandemic world.

Conclusion

Translating short-term resilience into long-term strategy

It’s an evolution, not a revolution: that’s just the way the sector works.

Over the course of the last year, universities have demonstrated strength and resilience. They have met the challenges of the pandemic with significant agility, embracing innovation and delivering rapid transformation. Their leaders will now need to make certain that the sector embraces these new ways of working whilst maintaining an open mind and welcoming innovation to ensure our institutions are fit for the future.

The last year has proved that it is possible to deliver academic learning without vast lecture theatres full of students; new modes of learning, teaching and collaboration are no doubt here to stay. It cannot be enough to simply put existing assets online, rather there needs to be a bottom-up approach to online and blended learning formats, putting students and the learning experience at the centre of education strategy.

Further challenges are inevitable, whether they are known challenges imposed by policy makers or unknown such as the pandemic. Retaining the sense of agility and fleetness of foot found as a result of responding to the pandemic will be invaluable in this context. Flexibility will remain the order of the day, in terms of the working and learning environments and in strategic decision-making.

Maintaining the increased levels of communication that have become the norm throughout the pandemic could be critical to success. The dexterity achieved through greater digital integration must be built upon, though not to the extent that it excludes all face-to-face interaction, whether that be amongst leadership teams or in the delivery of education.

At the end of this, we can’t revert to where we were beforehand.

As we move into a post-pandemic phase of economic, social and emotional recovery, it will be vital to have leaders in place who are able to adapt and refocus strategic direction while maintaining a clear eye on the shape of their institution. We must ensure that senior leadership teams have the breadth to carry the load as we move forward, in terms both of experience and qualifications and – perhaps more crucially – of their interpersonal skills.

Central to this will be ensuring clear delineation of responsibilities between the executive and non-executive. As we return to a mode of governance closer to pre-pandemic norms, it will be crucial to establish the right balance between the two, allowing them to fulfil their respective roles effectively.

Despite the turmoil and uncertainty brought about by the pandemic, our conversations with senior leaders across UK HEIs have left us in no doubt: this is a sector that will continue to thrive. The passion, dedication and commitment shown by leaders – and it must be said by staff at all levels – in universities the length and breadth of the UK underpins and confirms the sector’s resilience.

We were perhaps heading towards a new era of higher education in the UK. The pandemic has accelerated this transition and indeed acted as a catalyst for change.

Methodology

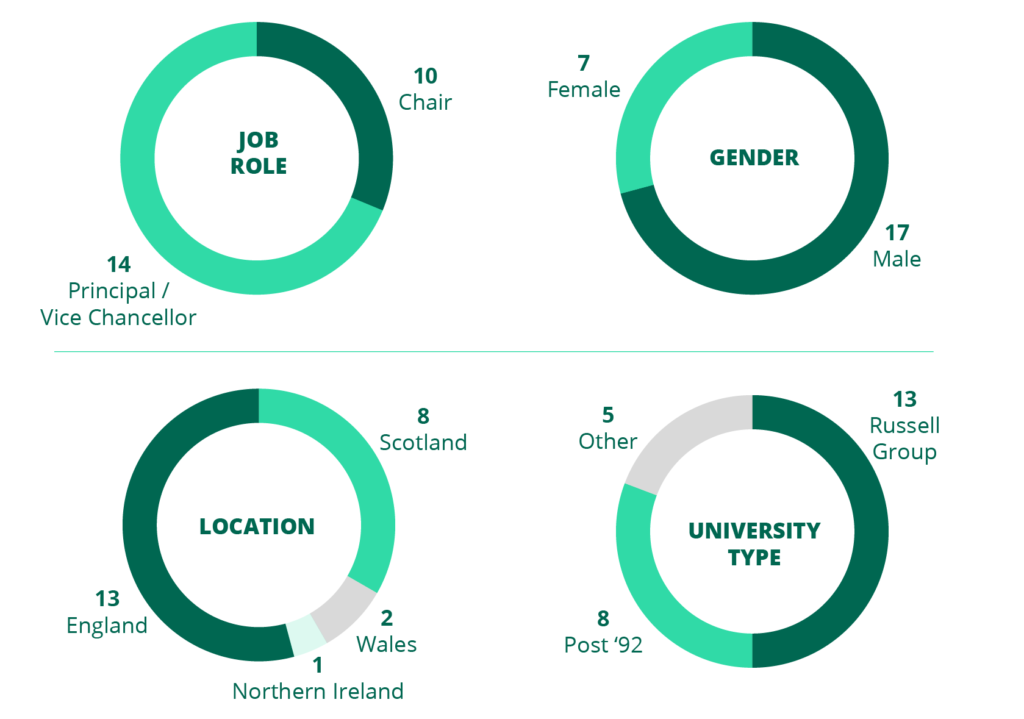

In producing this piece, we were fortunate to have the opportunity to speak with 24 senior leaders from UK higher education institutions. We spoke with a mix of vice-chancellors and chairs to ensure a balanced representation of the executive and non-executive voice. To ensure a mix of viewpoints and give the report balance, our interviewees came from a broad range of universities both in terms of their geographic locations and the type of institution.

We asked our interviewees to consider the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has altered the UK’s higher education sector and the ways in which senior leadership has been impacted by this change.

Interviews were conducted over Zoom, Teams and by telephone over a period of six weeks in early 2021.

Our questions were open-ended to give participants the opportunity to freely explore their thoughts and to provide their particular views. To encourage our contributors to speak openly and honestly, we assured anonymity. This ensured that we were gathering their genuine thoughts, observations and learnings. We have incorporated anonymous quotes throughout this piece to give an indication of thought and response.

Who we spoke to

Our dedicated Higher Education Practice

Saxton Bampfylde have advised universities on senior appointments for over 30 years, including over 180 vice-chancellor appointments globally. In the last two years our work includes the appointment of Professor Nick Jennings as Vice-Chancellor at Loughborough University, Professor Katie Normington as Vice-Chancellor at De Montfort University, Professor Andy Schofield as Vice-Chancellor at Lancaster University, and Victor Chu as Chair at University College London. Our work with HEIs is informed by our strong track record of appointing leaders in adjacent sectors. Recent examples include our work to appoint Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser as Chief Executive of UKRI, Professor Lucy Chappell as the Chief Scientific Advisor to DHSC, and current work to appoint the inaugural CEO and Chair of the Government’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA).

Contact

If you would like to find out how we can assist you with your next search or leadership advisory needs please get in touch.

Contact Jamie Wesley, Partner & Head of Higher Education

Visit our Higher Education Practice page